On Borrowed Time

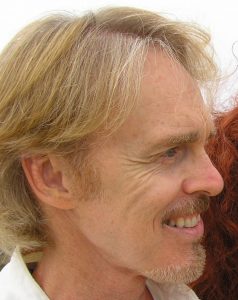

By Bryan Donahue and M. Rutledge McCall, this is the harrowing true story of a dying US Marine… and how he beat the same disease that took the life of American football superstar Walter Payton (no screen adaptation available at this time)…

PROLOGUE Ticking Bomb If you ever want to get fast, first-class service at a hospital, forget the emergency room—walk in the front door and collapse. I hit the floor in a dead faint and was instantly swarmed by orderlies and nurses. They instructed us to go to the ER, but I couldn’t move. When I came to, Lia was in tears, crying out for a wheelchair. For the second time in two months, her husband was dying. They rushed me to a room on 4 North and began running a battery of tests. I vomited and passed out on the CAT-scan table. The scan indicated that there was nothing wrong. Clean bill of health, right there. Even professionals make mistakes. When I came to, I was in such unbearable pain that I asked the charge nurse not to keep me alive. “Forty-eight over twenty-six,” another nurse was calling out my blood pressure. “What? Scan says he’s okay!” When your blood pressure is forty-eight over twenty-six, you are below comatose and barely above dead. That night after the medical team stabilized me, my wife dozed fitfully on a cot next to me. She awoke abruptly every so often and checked to see if my chest was rising and falling. When I came to early the next morning, the charge nurse was reviewing my charts and lab reports. She became increasingly agitated as she read through the file. She hurried out and returned moments later with a doctor. The doctor’s demeanor was somber as he analyzed the CAT scan and checked my vitals. Suddenly, he dropped everything and told the nurses, “We’re taking him in—now,” and began yanking cords and calling out orders. He wheeled my bed out of the room and into the elevator, where another doctor jumped on the bed and sliced into me with a scalpel. “Sorry about this,” he apologized tersely and ran a line into me. There was no time for pain killers. A few years earlier, when I was in the Marine Corps, my closest friend in boot camp had given me some advice that would echo into my future. One day at the end of a particularly grueling week of training, when I was feeling I couldn’t take much more, he said to me, “It’s all a game, Bryan. Don’t let them break you—if you break, you lose.” On the operating table that day many years later, I fought to recall his words as the anesthetic dragged me under and the world sank away from me. I was diagnosed with a rare liver disease called primary sclerosing cholangitis (“PSC”), a progressive hardening and scaring of the bile ducts that filter toxins out of the body through the bile. When the liver is badly damaged, it can’t re-grow enough tissue to heal itself—and you can no more live without a liver than you can without a heart. …Actually, no, you can live without a heart, if you have a mechanical pump. But there are no mechanical liver replacements. You do not live without a liver. Period. As a young man barely launching out into life, it was a frightening challenge to try to maintain an optimistic attitude while facing a life or death battle. Not to mention trying to remain hopeful that a cure would soon be found and that I might actually have a shot at living a long and enjoyable life. Instead, I was given three to six months to live. Talk about being hit in the chest with a sledgehammer. To put things in perspective, in February of 1999, just eight months after I was diagnosed, Super Bowl-winning running back Walter Payton—one of the top-five-ranked football players in the history of the sport—was diagnosed with the same disease. And he was dead by that Thanksgiving. If this disease could put a superman like Walter Payton in the grave in just months…what chance did I have? It takes a lot to make a Marine cry. All I could think about was the wonderful life I’d had on this amazing planet. I was going to miss it. Best 22 years a man could ever have. What I faced next was the hardest thing I’d ever done in my life: telling my family and friends. I cried like a baby, because I didn’t want to see them sad. And, I’ll admit, I was scared. Not so much because I was dying…but because I had just begun to really live. |