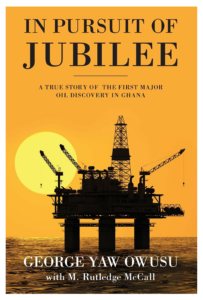

In Pursuit Of Jubilee

By M. Rutledge McCall and George Yaw Owusu, this is the riveting, true story of a $100 billion oil discovery in Western Africa, and the brutal, years-long battle that ensued to try to destroy and imprison the rightful owner of his share of the find (screen adaptation available, also written by McCall)…

“A great read and a thrilling ride! …a tale of dogged human aspiration, invention and the capacity to believe in the impossible. …This book is a testament to what people can achieve if their will never falters.”

– Rachel Boynton, Emmy and Tribeca Film Festival-nominated, Edward R. Murrow Award-winning Director; “Our Brand is Crisis”; “P.O.V.”; “Big Men” (Executive Produced by Brad Pitt)

To buy an autographed copy of this book at 20% below retail, click here.

PROLOGUE After waiting nearly two hours in a small, nondescript room at the Criminal Investigation Department (CID) headquarters in Accra, a group of uniformed and plainclothes police officials entered and escorted me and my lawyer to another room, where several dozen more police officers were waiting. One of the investigators informed me that, as part of their inquiry into various activities involving my company’s acquisition of offshore oil exploration rights in Ghana five years earlier, the court had issued search warrants for my home and my office. They were to be served immediately. Numb and disbelieving, I was escorted across town to my office in a convoy of police cars and a bus filled with armed, uniformed officers and with blue lights flashing and sirens wailing all the way. As we sped through the sweltering streets, Accra’s perpetual crowds of street beggars peered in through the windows, trying to get a glimpse of the criminal in the back seat. I was ordered to wait outside while investigators descended en masse into my office to the confused looks of my staff members. My attorney’s objections were ignored as officers confiscated files, computer hard drives, and countless documents. When they had taken what they wanted from my office, the speeding police convoy took me all the way down the Tema Motorway to my house, where my wife and our young grandson watched, frightened and helpless, as a phalanx of armed, uniformed officers and plainclothes detectives stormed in. Every room was searched, personal items pawed through, more computer drives taken, other documents seized, and every item photographed. It was embarrassing and degrading. I protested, of course, as any innocent man would who was being victimized by his own government. But it was no use. The day had not started out this way. * * * Tuesday, June 16, 2009, had been a seasonably humid day in Accra. I had just entered my attorney’s office when his phone started ringing. He waved me to a chair and answered the phone. I sat down. As he listened to the caller, a look came over his face that I’d seen enough times recently to know who it was. I mouthed the words, the CID? He nodded to me and said into the phone, “No, inspector. Mr. Owusu cannot come in again. Not today.” I felt my blood pressure begin to rise. I had just returned from an appointment with my doctor and here these guys were again, requesting another interrogation. I had been through a grueling session with the CID just the previous day. And the week before. These officers weren’t giving up. My lawyer listened again, then said to the investigator, “No. I told you. Mr. Owusu is on medication for high blood pressure and is under doctor’s orders to rest.” He covered the mouthpiece and whispered to me, “It’s about a form you forgot to sign after they questioned you yesterday. A minor matter. He says it will only take you a minute to drop by and sign it.” I shook my head and muttered something in Twi, my native Akan language. In Ghana, a country where the police were often seen as corrupt, nothing was a minor matter when the CID was involved. The officer on the phone was probably one of the same ones who had interrogated me several times during the past few days—sessions that had driven my blood pressure to deadly levels. They had questioned me over and over, about things I hadn’t done, crimes that had never happened, rumors I knew nothing about, and false accusations having to do with the efforts I had initiated five years earlier that resulted in the largest oil discovery in the history of Ghana. A discovery worth billions of dollars. Fittingly, as frightening as it was to be ordered in for interrogation by the police in relation to a series of felonies I was being accused of, the start of my career in the oil business had been even more terrifying. Nearly two decades years earlier and thousands of miles away, an explosion ripped through the Atlantic Richfield Company plant in Channelview, Texas. I was there and saw it all. It happened on a Thursday, July 5, 1990, at 11:15 p.m. during my shift at the ARCO plant. I had stopped to talk to another worker for a few minutes. While we were chatting, I received a call on my walkie-talkie from my supervisor. “George Owusu,” my radio squawked. “Come in, please. Over.” I grabbed my radio, clicked it on, said, “This is George. Over.” “I need you to check a valve on a tower on the plant grounds. Over.” While I received instructions on which tower and valve I had to go check on, the man I had been talking to got in his van and drove away. I pedaled over to the tower on my bike. No sooner had I climbed to the top of the tower and put my hand on the valve, when the plant erupted in a violent explosion and a fireball lit up the night sky. The plant looked as if a bomb had been dropped on it. Flames and thick plumes of smoke shot a hundred feet into the dark sky. Warped steel and wreckage was strewn all over the grounds. The explosion was felt several miles away, shattering windows in nearby houses and blowing out street lights. Neighbors a mile away reported a “flash like an atomic bomb.” The man I had been talking with just moments before the blast had arrived faster at his area because he was driving. As soon as he had gotten there, the explosion occurred. It would take days to find all of his body parts. I watched from the top of the tower a couple of hundred feet in the air as the horrific scene played out, terrified, not knowing what had happened. Trembling and stunned at the devastation around me, I somehow made it down the tower and got to the office, where I was warned that the explosion could be followed by a violent chain reaction. So we waited to make sure there wouldn’t be anymore blasts before we evacuated the plant. The plant’s fire brigade quickly arrived and began fighting the blaze. Hazardous materials units began arriving from the nearby Shell Oil Refinery. Harris County fire trucks were all over the place. Firefighters, ambulances, and police cars were pouring into the plant. Four dozen people had been on shift at the plant that night. The initial death toll was reported as 14. The total body count would reach 17, and would include several contract workers, and a tanker truck driver who burned to death in the cab of his vehicle as he tried to flee the scene. Five other people were badly injured, as well. Two cooling towers, a steam generation facility, a pipe rack, and two tanks were damaged. When I finally arrived home, my wife was waiting in the driveway. I fell into her arms and sobbed. I was diagnosed with post traumatic stress disorder and was admitted to therapy. It would be a year before I would be ready to return to work. The incident had literally been the explosive start of my new career in the oil business. The start of a nearly two-decades journey that would lead to police investigations thousands of miles away in Ghana, inquiries by the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ), charges of fraud, multiple interrogations by the CID, and half a decade of fighting for my very life and freedom. For me, the ARCO explosion was the beginning of one hell of a career. And now, 19 years later, with the police in Accra hauling me in for questioning again, the explosive end to my career had begun. My life was about to enter a long and bizarre battle as the new government of Ghana bore down on me, determined to see me behind bars, unfazed by the fact that I was also an American citizen. I suspected a couple of people who were probably behind the government’s relentless pursuit of me. People whose motives were not difficult to discern. One hundred and sixty billion dollars worth of premium grade crude oil was a powerful incentive. But what was surreal about what was happening to me now was that just six months prior to start of the CID interrogations, I had been basking in the euphoric glow of being fêted as a national hero. And the previous year, I was awarded the coveted Order of the Volta (an honor equal to the US Presidential Medal of Honor), bestowed on me by the government of Ghana for outstanding service performed for my country. As the police investigators pawed through my family’s personal belongings on that fateful June day in 2009, a hopeless feeling of government oppression settled over me at the realization that my own father had experienced something similar when a previous Ghanaian government had destroyed his life exactly fifty years ago that month. |